Somebody recently asked me what my favourite places on Earth were, and while my answer was almost imminent and without much thinking needed, I couldn‘t help but realise that those places had one main thing in common: I always find myself enjoying countries with very remote areas, like Chile, Argentina, or Sweden. It is in those places where, far from big cities and crowds, I truly appreciate the silence, nature, and sincerity of the place without any noise, traffic, or other distractions.

I currently live in a big city, though, and I am quite happy to be there. Escaping the city is like a luxury I too often like to treat myself with, and every time it feels like heaven. But that is eventually what it is: a luxury I can escape to, but making it an everyday reality is not what I want (just yet).

The truth is, there is also a lot of hardship and difficulties to find in rural or remote life. I could see this while I was fortunate enough to travel some of the most remote places on Earth. The reality of life there is troubled by often bad or lacking infrastructure and consecutive high costs, a limited job market, and high rates of under- and unemployment with consecutive poverty. And also, of course – otherwise, I wouldn‘t be writing here about this topic – there are also major implications on people‘s health and access to healthcare.

Remote – or rural – populations have to face major inequalities in almost all aspects when it comes to access to health care, whether it be access to facilities, medication or any kind of service.

Where and how many people live remotely from health care

In common language, ‚remote’ areas are considered to be far away from major cities and/or economic or health care centres. Typical remote areas are mountain areas like the southern Andes or the Himalayas, the Amazon basin, where basic roads simply do not exist, or drylands like the Outback of Australia or the Sahel region of Africa. As I have written about Caleta Tortel in my last post, access to the nearest clinic can take many, many hours by car (if there even is proper roads, let alone an ambulance service), and the main types of transportation (such as boats) might not be equipped for emergency situations. Area evacuation could theoretically be an option, but in places where there is no special funding or financial resource for those special operations, let alone an option to land or no trained rescue team, these types of transportation are simply not feasible. So even with optimal motorised transport, the nearest clinic is one or two hours away, and in case of having to rescue by foot, boat, or air, adequate emergency care is not possible. Furthermore, seasonal access can vary due to terrain or weather and further limit consistent and reliable access to healthcare.

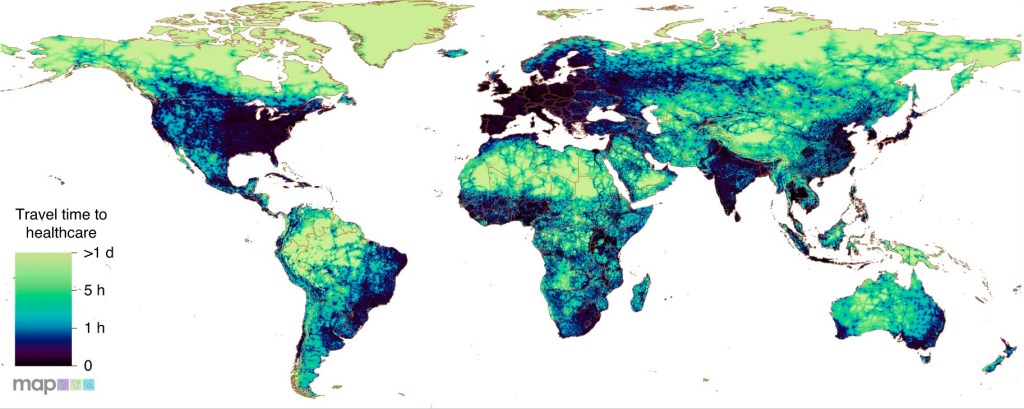

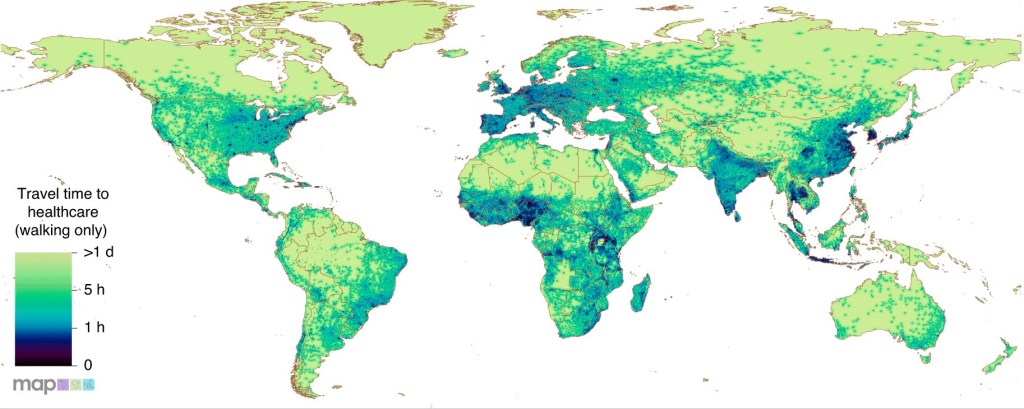

Now, theoretically, with access to motorised transportation, almost two-thirds of the world‘s population live within 10 minutes of a hospital or clinic and 91.1% even live within one hour’s travel time, as can be seen in the map of a study displayed below. This suggests a fairly (surprisingly!) good coverage of health care facilities in most areas; however, these numbers only reflect the time with the ‘optimal’ mean of transportation (whatever that means, since the authors have not stated if they expect every country to have the means and reality of dispatching helicopters everywhere). Everybody who has worked in rural hospitals, even in central Europe— rich countries— knows that the reality of travel times sometimes drastically and painfully exceed the ideal theory. The same authors also provided numbers for walking-only distances, which show that 14.2% of the world’s population live within 10 minutes of walking to a hospital, 39.8% within 30 minutes, and 56.9% of people live within 60 min of a healthcare facility by foot. Now, – disregarding that one hour is already a very generous time frame, considering that the desired time to treatment in the case of an ischaemic stroke should not exceed 20 minutes in an ideal setting – I still I felt like this was already quite a good percentage and it did not correlate with what I had experienced when talking to rural residents: Most people reported a greater subjectively ‘felt’ distance than what these numbers display of physical distance. Also, many people in need of health care attention are simply not able to walk or drive themselves to the next clinic, so it seems evident that the reality of ‘access’ is much more compromised.

Source: Mseke et al. (2024)

Source: Mseke et al. (2024)

How access in rural areas is limited: Accessability, availability, affordability and quality.

Now, distance and being physically remote is actually only one aspect and not the most crucial factor of accessing health care in rural areas. When speaking of ‚access to health care‘, there are actually more relevant and problematic reasons why people in rural areas cannot attain (not even basic) medical help and why people living in rural areas are actually excluded from health care in every sense.

It is estimated that for more than half (about 56%) of the global rural population basic health care is completely inaccessible due to inequities like financial disadvantages, impoverishment, poor legislation, or discrimination.

Without throwing a (at least not too big) side-eye to our favourite frenemy, the U.S.A., it is without discussion that legal right to healt, a national health system and legal health coverage are essential for equal and fair access to health care. However, on a global level, an overall lack of rights at rural levels can be observed, to the extent that in some regions simply no entitlement to health care exists. 38% of the global rural population do not have legal health coverage, and the lack of coverage is 2.5 times higher than in urban areas. As most of the world‘s already financially disadvantaged, poor or extremely poor people live in rural areas, the lack of legal rights also depends a lot on the level of income, and discrimination based on gender, age, and minority is common.

Rural populations also face inequities in the sense of uneven workforce distribution. Even though a lack of health care workers is a universal and global problem, shortages of health care workers, such as nurses, technicians, and especially physicians, are more pronounced as 70% of the globally missing staff is missing in rural areas. I can speak from experience when I say that the care health workers are able to provide is directly affected by their working conditions and, unfortunately, in rural areas low wages and safety concerns (as due to lack of protection gear, etc.) are still not sufficiently addressed and adapted to the circumstances and needs.

Another global problem is underfunding for health protection. Financial support of healthcare influences almost all areas of patient care, in the sense of waiting periods, acceptance or rejection of patients, quality of care, or availability of infrastructure and staff. Insufficient financing results in almost half of the world‘s population having limited access to health care, and rural areas experience twice as much underfunding as urban populations.

In addition to chronic investment deficit and missing money in health care, it is especially the poorest people that suffer the most. In settings where people are required to pay out of their own pockets, many people simply cannot afford the diagnostics or treatment needed, and if they do, it can mean further or complete impoverishment for them and their families.

These restrictions and limitations of access are directly reflected in health system outcomes, as, for example, in morbidity and mortality, when quality care simply cannot be provided. The maternal mortality rate in rural areas is 2.5 times higher than in urban areas.

Health literacy, which is reported to be generally lower in poorer and rural areas, is also a possible reason for people hesitating to consult health care services in remote places. As I have noticed, deeply ingrained beliefs (and objectively false beliefs, like putting sugar in your tea prevents diabetes – yes, I‘ve heard people say that!) can be dangerous and, oftentimes, rural populations lack education in order to properly question and distinguish between folklore, myth, and facts. Also, lacking awareness of their bodies, traditional and/or religious beliefs, and shame hinder people from properly realising when the consultation of a professional is needed. I have to highlight, though – according to my personal experience and conversation with people – it seems to me that people from most rural and developing countries would not reject modern medicine if given the opportunity. To me, the harsh rejection of modern medicine seems mostly a ‘first world problem’ and maybe even the product of being ‘spoilt’ by easy access.

Finally, all those factors influencing access to healthcare interact with each other. For example, long driving distances might cause elevated transportation costs, which can cause a bigger financial burden on rural areas. Poverty and socio-economic disadvantage result in little to no lobby, no incentive, and no voice for vulnerable people, leading to less funding, investment and a lack of legal interest, lack of rights, and lack of health coverage. There are also no incentives for health workers to work in poor and underfunded conditions, and a lack of health workers has been directly associated with worse patient outcomes, as maternity mortality in rural areas is strongly correlated with staff deficit.

What living remotely means for your health

Overall, distance – physical distance, as well as socio-economic and legal distance from the rest of society – has a direct impact on health and disease outcome. It can cause impossible adequate emergency care, delayed diagnosis, poor chronic disease managment, overreliance on traditional or informal medicine, gaps in vaccination and prevention as well as gaps in providing and caring for mental health.

The place of residence determines wheter you have access to adaquate health care or significant disatvantage. It can even determine wheather you live or die.

But how is it for healthcare workers to work in such remote places? More on that in my next post!

Sources

- Mseke EP, Jessup B, Barnett T. Impact of distance and/or travel time on healthcare service access in rural and remote areas: a scoping review. J Transp Health. 2024;37:101819. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2024.101819.

- Scheil-Adlung X, editor. Global evidence on inequities in rural health protection: new data on rural deficits in health coverage for 174 countries. Geneva: International Labour Office, Social Protection Department; 2015. (Extension of Social Security Series; No. 47)

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. (WHO guideline). Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341130/9789240025318‑eng.pdf

- Weiss DJ, Nelson A, Vargas-Ruiz CA, Gligorić K, Bavadekar S, Gabrilovich E, et al. Global maps of travel time to healthcare facilities. Nat Med. 2020;26(12):1835–8. doi:10.1038/s41591‑020‑1059‑1.