For me, Patagonia is one of the most beautiful places of the world. There, you get to know raw nature, untouched glaciers, harsh mountains, endless fields of „pampa“ and silence on your ears so loud, it can be deafening. You can truly immerse yourself in nature and you can hike or even drive for hours without meeting one single human soul. The villages you will find there are scattered and remote from everything. People living there get used to being far away from everything and they enjoy their peace and tranquility.

Since the first time I had travelled to Patagonia, it had been a dream of mine to get to know „Carretera Austral“, or „Ruta 5“, a road that goes along the chilean side of Patagonia until you can’t go further by land, making it one of the most distant and remote areas you can get to know in the southern hemisphere.

This year, I finally fulfilled this dream of getting to know this part of the world. We started off in february, at first hitchhiking south, and when we no longer encountered many cars that could take us, we were stranded for hours hiking alongside the road in complete solitude. We finally rented a car ourselves and went on driving on our own until the very end. Ruta 5 ends in Villa O‘Higgins, the southernmost town of Chile that can be reached by car. If you want to go further south, you need to either cross the border to Argentina or embark on a ferry, which takes you around 48 hours through the Patagonian fjords to the 12th region of Chile, „Magallanes y de la Antártica Chilena“ – yes, you read correctly – Antarctica – it‘s this remote we are talking about.

Caleta Tortel – living truly remote

As almost every other village we had seen, Caleta Tortel, the village where we embarked o the ferry, is far from everything – however, even further than others, since it is not even built near Ruta 5, but on a side street and once you get to the town there are no roads to drive on, only wooden walkways on stilts . So, by the time we got to Caleta Tortel we had already been exploring Patagonia for about three weeks and we had been distant from any kind of infrastructure for quite some time. However, this level of remoteness was something else. I could‘t help but think „How would an amulance get here? How the hell would you bring someone to the next cardiac catherization laboratory? Where even is the next cardiac catherization laboratory??“.

I think there might be some kind of a curse that was put upon us as doctors (or health care professionals in general) the moment we got to wear – our unversally ill-fitting – hospital attire for the first time, sticking with us for a lifetime: A curse that makes us think constantly, whereever we go and to whoever we talk to, about medicine and what might happen that could turn a perfectly healthy human being into a patient.

So, of course, when travelling Patagonia, my carefree-non-medical-boyfriend would often say „What a beautiful place, so peaceful, I enjoy having no cell phone service“, and I would often answer, „Yes, but what if you had a stroke right know?“.

Discovering medicine all around us: Necessity to survive

So this was the situation in Caleta Tortel of course. What I did not expect, however, was that, as magical as Caleta Tortel is, it had already the answers to the question I had not yet asked: All around the town we could find small signs in front of all kinds of plants and bushes describing their medical properties and possible applications for us. The village was full with knowledge about native plants to cure daily complaints of its inhabitants. Not only that: when we entered a small restaurant we found books and reports about herbs and plants being used in the medical knowledge of the locals living there for decades or even centuries.

The unique and remote location, between glaciers, rivers and the sea caused people to have a special relationship with nature. With no road access and boat journeys taking days to reach the nearest towns, modern medicine was slow to arrive. There was no health post, let alone a rural clinic. Medicine, in the conventional sense, was very limited and in order to survive people had to rely on what was around them: herbs and plants, or as they called them „Yuyos“.

It was in this setting that I stumbled upon a small booklet compiled by the local Ventanal Aysén. It featured interviews with elderly residents who still remember the traditional use of native plants. These weren’t academic studies or systematic records, but living oral histories — fragments of ethnobotanical knowledge either gained by pure experience in the face of survival and/or then passed down, inherited by generations. It was especially women who had gathered this knowledge, and it was them who tended to their gardens. Daughters learned from mothers, who learned from their grandmothers and it was shared with those in need, spread throughout the community.

Reading through the pages, the interviewees were conscious about this ethnobotanic knowledge being at risk of being forgotten. I found these stories to be a beautiful tribute to the women who held this wisdom and to a culture of resilience that existed long before doctors and health posts arrived.

Survival and the Need for Prevention

There is something I only truly understood once I recognized the phytochemical properties of the plants and their physiological effects on the body: many of them contain substances with preventive health benefits. The extreme remoteness of these communities made prevention — rather than cure — the foundation of health. With no access to emergency care, the goal wasn’t to treat illness once it appeared, but to stay healthy in the first place. The focus was on maintaining health and assure healthy aging. As simple as it might sound, the best chances of survival in a remote place is not getting sick in the first place..

Couriosities and myths

Some of the stories seem incredible and the reported healing can most propbably – if not most certainly – be attributed to pure luck and coincidence. Like the story told by one person who cured his wound by peeing on it. Or the story where they regularly used horse dung to brew infusions to heal colic (or was it the first Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for C. Diff infection? ;)). Some also told a story about using a Condor‘s heart or a bezoar of Guanaco to treat fright – it can be argued that you need courage to use those ingredients and even more so to ingest them, so yes, maybe this could be a valid method?

Understandably, some methods seemed so incredible and supernatural that people used to call those „Yuyeros“ witches or wizards. And even though some stories might remind of magical realism, as Ventanal Aysén noted – some of their healing properties are actually more reality than magic.

Everyday complaints and common plants

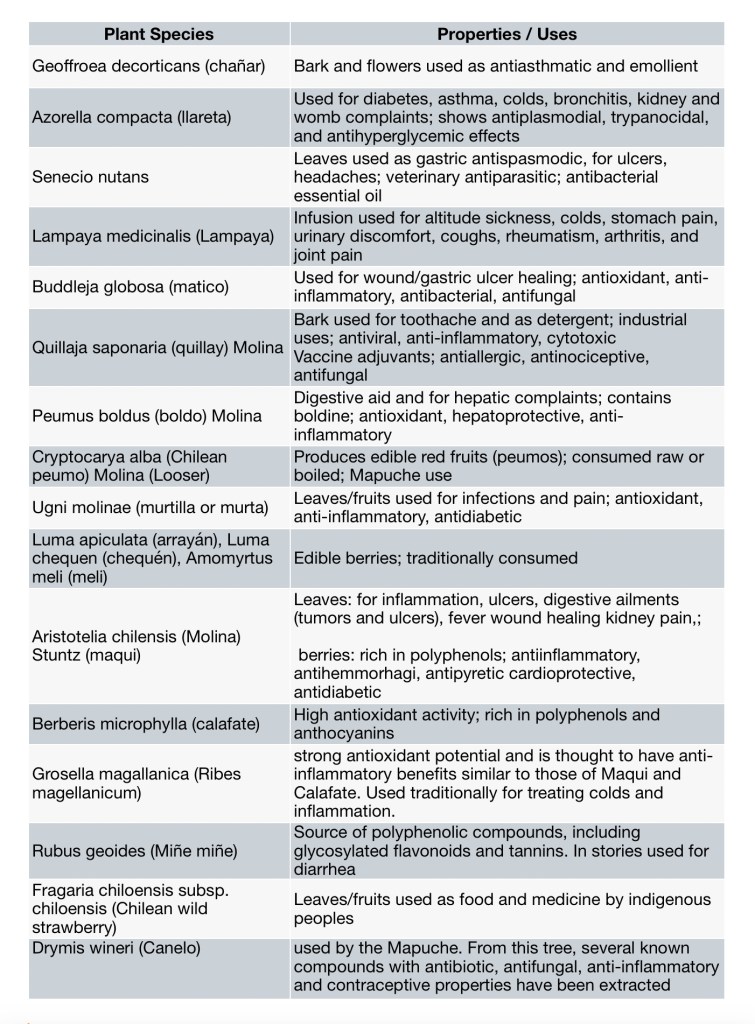

Many plants described in the Yuyeros’ booklet are commonly known, such as eucalyptus, mint and lemon balm. Other fruits are endemic to Chile, such as Calafate, Grosella and Maqui, some plants are specifically known in indigenous culture like Quilloy, Arrayán, Miñi Miñi and attentive Harry Potter readers might already have heard about common wormwood, Ajenjo.

Besides being known for promoting health and generally being considered ‘healthy,’ these plants are stated to be commonly used by the Yuyeros to treat everyday complaints like fever, colds, pain, or digestive issues.

Background

But what is truly behind these ‚Yuyos‘? Is it only myths, coincidence or might some of them hold genuine medical value?

To my honest surprise, when researching naive plants of Chile I found that quite some of them have been scientifically studied – and that everyone of us should maybe eat more berries!

I‘ll explain:

Some plants contain certain bioactive agents – particularly polyphenols such as anthocyanins or flavonoids – with antioxidant properties, being linked to anti-inflammatory or even chemopreventative, anti-diabetic and gastroprotective and/or antimicrobial potential:

These antioxidant compounds help combat oxidative stress, which is linked to chronic diseases like cancer, heart disease, inflammation, arthritis, immune system- and cognitive decline or cataracts.

Those phytocharacteristics were found in fruits such as Murtilla, Arrayán, Calafate, chilean blueberry, chilean wild strawberry or Boldo, amongst others. Studies have shown the extracts of these plants to inhibit lipid peroxidation in erythrocytes, show anti-aggregation activity in platelets, act as radical scavengers (neutralizing harmful molecules) and also stimulate bile production for digestion.

Furthermore, the equally resulting anti-inflammatory properties, specially in Maqui and Calafate (related to their especially high concentraton in anthocyanins), are notable as studies have found that their extracts prevent inflammation related to obesity: The inflammatory response induced in adipocytes and macrophages is inhibited on a cellular level, and the expression of adipokines is reduced. The same might be true to Grosella and Murtilla as well, since they also show a high antioxidant activity, though research is limited..

Maqui is also the most studied plant also in terms of anti-diabetic properties and positive effects on metabolic syndrome. Studies were able to show the prevention of oxidative stress in human endothelial cells, as well as improvement of the overall glucose metabolism and tolerance in both experimental models and diabetic patients. Other plants like Arrayán, Calafate, and Boldo may offer similar benefits due to overlapping phytochemical profiles.

Lastly, these same polyphenolic compounds have shown gastroprotective potential. The resin of the iconic chilean national tree, the Araucaria, is also commonly used in indigenous culture for treating gastric ulcers. A study found two of its phytochemicals to be comparable to Lansoprazole, a common state-of-the-art drug used in modern medicine.

So, as you can see, Maqui and Calafate seem to be potential superfruits, and since similar phytochemical properties can also be found in Grosella, Arrayán, Boldo, chilean Blueberry and chilean Wild Strawberry

My personal takeaway is that ‚traditional medicine‘ does not mainly aim at or pretend to replace modern medicine – its more about managing with the limited resources people have at hand and about consciously paying attention to ethnobotanic beneficial effects in order to promote a healthy aging and longevity. Prevention is an important – if not the most important – aspect of a healthy life in remote areas. Yuyos are not a replacement for modern medicine, they work alongside it.

Secondly, people living in remote areas are aware about the remoteness of their home and they are conscious of it. They can see sickness and death as a natural part of life — not something to fear, but something to understand. Maybe the fear of sickness and death is a luxury we‘ve aquired in modern days, where sickness and death is not visible anymore.

Nature has taken us so far and still, modern medicine is a luxury not everyone has. We, who have access to an emergency room within a few minutes and not take it for granted. Prevention is better than treatment and even though modern society might often forget, we have to remind ourselves of the impact that our own habits and lifestyle can have on our health.

Sources

- Servicio de Salud de la Región de Coquimbo . Entre yuyos y brujos: uso de hierbas y medicina tradicional en habitantes de Caleta Tortel. Santiago, Chile: Servicio de Salud; abril 2025. Disponible en: https://www.sfgp.gob.cl/sites/www.sfgp.gob.cl/files/2025-04/Entre%20yuyos%20y%20brujos.pdf

- Ruiz A, Hermosilla C, Romero ME, Walter T, Muñoz M, Devoto L, et al. Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and biological activities of native Chilean plants. Curr Pharm Des. 2021;27(9):1134–68. doi:10.2174/1381612826666201124105623.